|

The age of the genuine theatrical stinker is over. But there are still

plenty of terrible things to watch out for ...

|

|

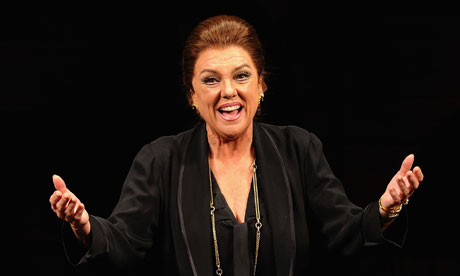

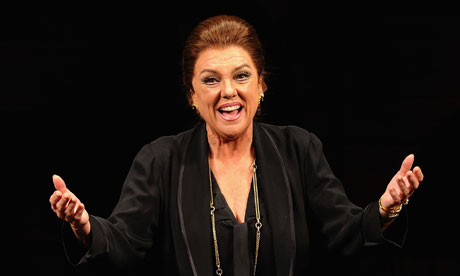

Bum notes ... Tyne Daly as Maria Callas in

Master Class at Samuel J Friedman Theatre, New York.

Photograph: Dimitrios Kambouris/WireImage |

In all the recent controversy about whether British theatre has become

more risk-averse as a result of the recession, one fact has been

overlooked: the virtual disappearance of the truly bad play. This has

happened for a simple reason. Production costs are now so high that

commercial theatre can no longer afford to mount the kind of rubbish

that was a staple part of my early reviewing life. And why would anyone

go out and see second-rate theatre when they can stay at home and watch

second-rate television?

Lousy plays used to come in two forms: drawing-room comedies and

thrillers. The former were an anaemic aftermath of the great NoŽl Coward

tradition, and dealt with such pressing matters as debs seeking ideal

spouses, dispossessed gentry slumming it in a Belgravia mews, or butlers

standing up for conservative values against mildly progressive

employers. Even worse were the whodunnits and thrillers which, if

English, took place in snowbound country houses and, if American, in

isolated Nantucket beach residences. After the success of the genuinely

good Sleuth and Deathtrap, by Ira Levin, one thing was also inevitable:

no corpse would take death lying down ever again.

But, even if the bulk of new writing now comes from the subsidised

sector, it is still in danger of breeding its own cliches. Following

humbly in the wake of the great American critic George Jean Nathan, who

once produced a list of the portents of a bad play (eg "When, as the

curtain goes up, you hear newsboys shouting Extra!, Extra!"), I append

my own list of contemporary signs, whether in new plays or classic

revivals, that audiences are in for a rough evening:

1. Any play in which a character aggressively masturbates within two

feet of the front row.

2. The moment a child emerges from an upstairs room to describe, in

graphic detail, his or her bad dreams.

3. Any site-specific show that seeks to intimidate the spectators by

asking them to pose as concentration-camp victims or inmates of an

institution to be pursued down darkened corridors by chainsaw-wielding

figures.

4. Plays that treat sad divas (Judy Garland, Maria Callas) less as

specific examples of showbiz misfortune than as tragic emblems of

suffering humanity.

5. Plays that invoke memories of Fred West, Josef Fritzl, the Soham

murders or the abduction of Madeleine McCann as an excuse for

titillation without offering any compensating psychological

illumination.

6. Any revival of a period comedy in which it takes approximately

seven-and-a-half minutes to get to the delivery of the author's first

line.

7. Productions that start with an ear-splitting burst of pop music to

announce their urgent contemporaneity.

8. Plays in which a run-down, travelling circus becomes a metaphor for

cultural decay.

9. Family dramas in which parental sexual abuse is saved until the

denouement, and produced like a rabbit from a hat, to explain the

preceding two-and-a-half hours of unrelenting misery.

10. Any play in which defecation is used to cover up dramatic defects.

This is a highly personal list, to which I'm sure you can add. But it's

a reminder that, even in an age when rank bad plays are far rarer than

they were in the age of commercial profligacy, the type is not wholly

extinct.

Do read: George Jean Nathan, Encyclopedia of the Theatre (Farleigh

Dickinson Press) |