|

Opinion articles on 'Madeleine'

Madeleine by Kate McCann, 14

June 2011

|

|

Madeleine by Kate McCann

By John Blacksmith

Tuesday,

14 June 2011 at 00:10

Hopes that the extreme caution with which the McCanns have previously discussed

the disappearance of their daughter might be moderated in Madeleine take something of an early blow: in the acknowledgements

section M/S McCann credits, in addition to the normal celebrity quotient of editors, agents and publicists, no fewer than

four lawyers (including Mr. E "Expunge" Smethurst and Adam Tudor of Carter Ruck) and thanks them not merely

for their assistance but for their part in completing the book.

They

may, of course, just have been refreshing her memory of the litigation that the couple has been involved in since 2008; or

their collaboration may have taken a different form. Whichever it is their silent presence in the gap between page and reader

suggests that both newsworthy revelations and glaring inconsistencies are going to be in short supply. Nevertheless for students

of the case the book is a worthwhile read, first and least valuably as a memoir, secondly as a historical source and lastly

as a self-portrait.

Regarding the first, as a simple celebrity-cum-misery memoir

it isn't bad at all. M/S McCann eschews the use of a ghost writer and, despite what we've read of her execrable "diaries",

knows how to put a sentence together. The early pages, indeed, are the best and least self-conscious in the book as she writes

lightly and without sentimentality of her Liverpool background and childhood.

Her

descriptions of student life and the early years of her relationship with Gerry McCann are less spontaneous, singing more

of the celebrity literary agents' demand for background colour than any strong desire to share her memories. Life in New

Zealand and the Netherlands floats by with almost no comment on the culture or population of the two countries, in contrast

to her tale of attempts to have children which, as an erstwhile obstetrician, she recounts in considerable detail. About medicine

as a vocation she has nothing to say and none of her patients are ever portrayed, anonymously or otherwise. She writes that

she had no particular interest in a medical career — it was more a matter of deciding between the various opportunities

that her undoubted academic ability and determination (and she is modest about these) offered her. With the birth of her children

the conventional narrative of early ambitions achieved and human happiness attained is complete. Despite the unoriginality

of the tale — which is the fault of the industry, not M/S McCann — this is an adult speaking, not a celebrity

creation, comfortable with her judgements and decisions and, up to a certain point, confident in her identity.

Thus the curtain is raised on the drama the reader is most interested in: between May and October 2007 M/S McCann suffered

the loss of her daughter, became a world-wide "misery celebrity" with unrestricted access to the corridors of the

great and a developing taste for travel in private jets and then, in an altogether Hitchcockian twist, was accused of involvement

in the disappearance of her own child before finding eventual sanctuary in her homeland. This transformation in her fortunes

was matched, at giddying speed, by her portrayal in the media — from glamorous but stoical heroine to a rag doll stripped

of all privacy and dignity in a matter of weeks. How she and her husband handled these switchback changes in their fortunes

together with the public's perception of events provides the heart of the book, with the police investigation into their

possible guilt provoking the most strongly felt and dramatic writing in the whole work.

Soon after their return to the UK the drama is essentially over. The pathos of Clarence Mitchell's press conference in

front of their Rothley home, with the pair standing mute in his long shadow like a pair of dejected, sagging, criminals, remains

sharp in the memory. Behind the scenes, however, and starting with a three and a half hour legal defence meeting on the day

they landed in England, one of the most expensive and powerful legal teams in modern British history was being assembled.

Given the paucity of the Portuguese police case against the pair — a large box full of loose ends — the defence

effort seems disproportionate to any actual danger that threatened them and the tension inevitably falls away. What follows

becomes something of a public report in which her campaigning work in child protection and her various interviews and public

appearances are described in considerable, not to say tedious, detail. Meanwhile the exhausting, exhaustive and at times hysterically

absurd campaign to find her daughter uncovers absolutely nothing, nada, not a single lead.

Personalities are naturally described in limited — i.e. non-existent — depth according to the conventions of the

genre. It is not easy for it to be otherwise when writing about living people who may still have a part, however obscure,

to play; Goncalo Amaral, unsurprisingly, is the subject of scorn and bewilderment at his supposed lack of human feeling and

his determination, according to Kate McCann, to stop the world searching for Madeleine. Little is said, though no doubt much

could be written, about the various chancers and scoundrels who offered their services — at a price — to help

locate the child.

Despite the collaborating lawyers and the ever-present sensation

of a text having being under microscopic scrutiny before being allowed to reach the paying reader there are one or two minor

surprises. The extremely active role of the grandly named but only recently founded International Family Law Group in the

parents' affairs in the early days, including their part in the establishment of the controversial family fund, their

pressing suggestions that Madeleine should be made a ward of court and their introduction of some serious mercenaries-cum-

private investigators from the Control Risks group, is bound to raise questions about their judgement. The IFLG was also intimately

involved in the couple's ill-fated legal move to lay hands on Leicester police files on the case in summer 2008. M/S McCann

gives a brief extract from the (previously confidential) Leicester police response to the action which stated, essentially,

that there was "no clear evidence" to eliminate the couple from involvement in the child's disappearance and

therefore they would not entrust them with the requested files. The LP position remains unchanged: the files are still denied

to the parents.

M/S McCann's feelings of having been abandoned by British "authorities"

— she doesn't really do the separation of powers thing — once she is made arguida are revealed as the mirror

image of Amaral's sense of abandonment by his own chiefs, though no doubt some readers will see deep currents beneath

the apparently obvious truth of her comments. She explicitly denies any premonitions about Madeleine's well-being in Praia

da Luz — somewhat surprising given the equally explicit statements of some of her friends on the question. And new to

me, at least, is the Portuguese police claim that a witness saw her and her husband carrying something in a large black bag

on the evening of May 3.

The conclusion of the book exhibits a certain tension.

The celebrity/misery memoir rules demand an upbeat ending; M/S McCann is OK with that but is uneasy about how the public might

judge her if she is, well, too happy, given the circumstances of a missing child, fate unknown. Still, she manages

it well enough, just as she manages the burden of her guilt. The knowledge that she is a stronger and more able woman now

than she was a couple of years ago helps her, she says, to "shake off" a little of that guilt. Such questions as

the real meaning of guilt, together with Kate McCann's Catholic conception of it, take us away from the celebrity memoir

and on to the much more complex area of Madeleine's value as a true self-portrait, a subject that we will soon

turn to. For the moment we can leave her with her book successfully completed, staring sensitively into the distance, alone

— apart from the presence at her side of Bill Scott-Kerr, Sally Gaminara, Janine Giovanni and Alison Barrow, all of

Transworld publishers, Neil Blair and Christopher Little, her agents, the aforesaid quartet of lawyers and her friend Claudia

from the Portuguese PR company Lift Consulting — sad but beautiful, stronger for her suffering. Cue music and credits.

|

Madeleine: Wherein lies the Truth, 15

June 2011

|

|

It is said there is often a lot of nonfiction in fiction and

a lot of fiction in in nonfiction. Kate McCann's new autobiography, Madeleine, is a prime example of this axiom.

I say 'autobiography' because Kate's book is not so much about what happened to her missing daughter, Madeleine

Beth, but about Kate McCann nee Healy - her life, her loves and her losses, her trials and her tribulations. In reality, very

little of the book is about the missing little girl who vanished in Praia da Luz, the lovely vacation destination in the Algarve

of south Portugal; it is a carefully crafted revisionist history of one of the most puzzling missing children's cases

in recent years and a strident defense of the characters and behaviors of Kate and Gerry McCann.

Children go missing every day around the world but few children get

the level of publicity that has surrounded the case of Madeleine McCann, who was almost four-years-old the evening she vanished

from the McCann's Ocean Club apartment, allegedly snatched from her bed as she slept in a bedroom with her twin two-year-old

twin siblings, Sean and Amelie. What set this case apart from so many is the fact that her parents were not at 'home'

with their children when this alleged abduction occurred; they were off in the resort complex dining and drinking with their

seven friends for the evening. For that matter, all of the infant and toddler children of the Tapas restaurant party were

left alone to fend for themselves while their parents enjoyed their last night in town.

Madeleine and her brother,

Sean, had spent a good hour of the previous evening crying for their parents and a couple of the other children were fussy

or ill, one to the point of vomiting while her parents were off having dinner. Three of the families locked up their apartments

while they were gone, but the McCanns, Kate and her husband, Gerry, say they left all the doors open so that someone, apparently

anyone, could have easy access to the children. The parents of these children were hardly uneducated boobs. They were medical

doctors and surgeons and folks of relatively high status back home in their British communities. The case made the tabloids,

but, in fact, it was the McCanns themselves that courted the media relentlessly, making Madeleine the most recognized missing

child in the world and, themselves a target of a good deal of criticism and skepticism. They claimed their campaign was to

find Madeleine but a fair number of people think it was a smokescreen to cover their own criminal acts.

When Madeleine turned up missing at the end of the evening's

revelries, the world was not only shocked that the little girl disappeared but that her parents were neglectful in their duties

to provide a safe situation for her. Not only that, but rumors began to fly that the McCann children may have been sedated

by their own parents so as to not be problematic again when left unattended and with that additional bit of disturbing information,

the McCanns became victims and villains at the same time. Over the course of the next few months, the police came to believe

that the only victim in this drama was Madeleine who they surmised died accidentally while left alone and that the McCanns

hid little Madeleine's body somewhere in Praia da Luz, staged an abduction, and with the help of their friends covered-up

the crime. Four years later, the case remains unsolved and the McCanns remain under suspicion.

Which is why Kate

McCann wrote her book, Madeleine. Not, in my opinion, to re-energize the search for her daughter as she claims, but

to convince people of her innocence and raise revenue. Considering the fact the book sold 50,000 copies of the very first

day and was serialized for half a million dollars and the Amazon reviews are mostly glowing and supportive, I would say Kate

has achieved her goals in quite a smashing way.

But, there are still hidden nuggets of gold to be mined from within

Kate's version of what happened in Praia da Luz on May 3, 2007. The one dangerous thing about telling yet another rendition

of events is that there is often truth among the lies or lies among the truth; this is why police investigators always want

persons-of-interest to keep talking and defense attorneys keep telling their clients to shut the hell up.

The added information in Kate's book has enabled me to complete

a Profile of the Disappearance of Madeleine McCann (only buy the UPDATED version available in the next 24 hours). I had been reluctant to offer one for a long time because,

in spite of the many police reports and statements and television appearances of Kate and Gerry McCann, I wanted to hear the

story from one of their mouths, to know their answers to some very pertinent questions. Kate finally did me the favor when

she wrote, Madeleine, and although most of the book is a defense of her behaviors and actions, it is through this

defense that Kate has given me a much stronger insight into what likely happened the night Madeleine went missing and why

certain things happened or did not happen. Even with time to meticulously choose what one wants to say, it is amazing that

what actually ends up coming out is something that perhaps would be better left unsaid. However, personal agendas, narcissism,

and a lack of objectivity can cloud the judgment and the end results might not be exactly what the person intended. And I

thank Kate for that.

Let me tell you two of the biggest revelations in the book: Kate admits no one came through

the window of the children's bedroom. Yes, after years of insisting that someone broke into the apartment by tampering

with the shutters and forcing the window open, Kate now backs down from that claim, agreeing with the Policia Judiciara that

an abductor did not climbed into or out of the room. This is sort of a Bombshell Tonight. What this means is that Kate does

not claim the police botched the evidence and while she still claims there was an abductor that opened the window for reasons

that make no sense, her admission changes how I view what actually happened that night.

Another fascinating bit

in the book is Kate's incredibly generous forgiveness of Jane Tanner for not telling her immediately that she saw a man

carrying Madeleine off from the apartment; she is instead thankful that "someone had seen something." In other words,

Kate is happy an abduction was seen going down, not that she was notified of it in time to do anything about it. This startling

revelation tells me a lot about the mindset of the McCanns and adds greatly to the profile in determining what happened to

Madeleine.

I hope Kate McCann does achieve her goal of re-energizing the investigation of the disappearance of

Madeleine McCann and that the truth of the matter will indeed finally come to light.

|

'Lie With Me Mummy', 17 June 2011 |

|

'Lie With Me Mummy'

EXCLUSIVE to mccannfiles.com

By Dr Martin Roberts

17 June 2011

'LIE WITH

ME MUMMY'

With you, for you, and about you petal.

For openers

Kate McCann's revelatory autobiography adds remarkably little to what was already known about daughter

Madeleine, despite claims that it was written to help the search for her (helping 'the search' and helping

others to search are not quite the same thing). What it does do, categorically and, one might add, rather usefully,

is to confirm the falsehoods originally put in place over four years ago. It is an artfully choreographed confection, liberally

sprinkled with lies, blatant and subtle, and topped of with a dash of hypocrisy.

Within the first couple of pages

Kate McCann identifies herself logically with/as the 'abductor' of her daughter:

"I wanted to make

sure that they (the children) would always have access to a written chronicle of what really happened." (p.1)

"Others have seized the opportunity to profit from our agony by writing books about our daughter, several of

them claiming to reveal 'what really happened.' Which is extraordinary, given that the only person who knows

this is the person who abducted her on May 3, 2007." (p.2)

It is important to understand that since the

author's arguida status was lifted she has had the time and the money both to translate and to scrutinise the Portuguese

police files made publicly available in the Autumn of 2008. Indeed she is careful to point out to her readers how she has

invested many months and close to £100,000 in doing so, reading them in 'microscopic detail.' It follows that,

quite apart from being the only person who knows what really happened, she has benefited from exactly the same access to accumulated

background data as anyone else might. There are no excuses whatsoever for errors of fact appearing in this collaborative 'account

of the truth.' If any should appear then they have been sanctioned so to do. That makes their inclusion deliberate. And

a knowingly incorrect statement is, by definition, a lie.

Let the author lift the curtain on her own performance

therefore:

"As a lawyer once said to me apropos another matter, 'One coincidence, two coincidences - maybe

they're still coincidences. Any more than that and it stops being coincidence." (p.328).

Not unreasonably,

we might apply this same 'three strikes and you're out' rule ourselves, beginning with a small test of Kate McCann's

numeracy. After all, her entry in the Dundee University yearbook when she graduated in 1992 concluded with the line: 'Prognosis:

mathematician and mother of six.' (p.10).

1. "In January 2004, when Madeleine was seven months

old, we rented out our house and moved for a year to Amsterdam..." (p.31).

2. "On the afternoon of

1 February 2005, Sean and Amelie made their appearance in the world...A few hours later, Gerry brought Madeleine

in to meet her little brother and sister. Just twenty months old herself at the time, in she came in her cute lilac

pyjamas and puppy-dog slippers." (p.37).

3. "On Madeleine's sixth birthday, 12 May 2009, I met Isabel

Duarte for the first time." (p.338).

Taking last things first, why should readers need confirmation of Madeleine's

date of birth so late on in the book? Could it be due to the uncertainty engendered by the author's earlier calculations?

Unless one counts only to the last completed month, Madeleine would have been nearer eight months old in January.

The same question arises in connection with statement no. 2. Even as early as the first of the month, Madeleine could not

have been 'just twenty months' on 1 February 2005, if she were born on 12 May, 2003. She would have been

well into her twenty-first.

May 12 is not the only date to give Kate McCann pause for thought. May 3 is another.

And not only on account of its obvious associations with Madeleine’s being 'taken.'

Here are three

further statements with a suggestive connection:

1. "She had addressed me as Kate Healy, and although

this was the name by which I was always known before Madeleine's abduction, since then I'd only ever been referred

to as Mrs McCann." (p.189).

2. "On 4 May 2007, I became Kate McCann. According to my passport,

driving licence and bank account I was Kate Healy. I hadn't kept my maiden name for any particular reason - it was just

who I was and who I'd always been. But when Madeleine was taken, the press automatically referred to me as Kate McCann,

and Kate McCann I have been ever since." (p.349).

3. "One of the big changes in our life has been the

loss of our anonymity...As Kate Healy, I could do what I liked, when I liked, talk to whoever I wanted to talk to,

behave naturally without feeling I was being judged by those around me." (p. 356).

With a bank account in

her maiden name of Healy, it seems only fair to suppose that Kate signed her cheques in that name also. She didn't 'become'

Kate McCann until 4 May, after Madeleine went missing. And yet on several occasions, including May 3 2007,

she signed the Ocean Club creche registers as K. McCann.

When do such anomalies cease to be coincidental?

"We'd never lied about anything - not to the police, not to the media, not to anyone else." Says Kate (p.205).

Start as you mean to continue I suppose. 'Jemmied shutters' anyone?

By way of introducing some variation

into the process, instead of telling three slightly different tales to encompass the same lie, you can always repeat one lie

three times:

"...since there is no law enforcement agency at all actively inquiring into her (Madeleine's)

disappearance." (p.4).

"...we have not been prepared to accept the platitude that work in Portimao continues

when we know this is not the case." (p.364).

"Since July 2008 there has been no police force anywhere

actively investigating what has happened to Madeleine." (p.364).

The Leicestershire Police position as at

June 2011 is as follows:

"Anything in relation to the investigation into the disappearance of Madeleine

McCann will not be released whilst it remains ongoing.

"...it is also necessary to look at the

impact on the ongoing investigation of such disclosures. It is impossible to say until the operation is concluded

which information may or may not be relevant to any future prosecutions."

"We are the only people looking

for her." (p.364). That much remains true. I wonder why?

"If a review is declined, or indeed if no decision

is ever made, we will be left with no alternative but to seek disclosure of all information possessed by the authorities relating

to Madeleine's disappearance." (p.367).

They might as well save their energy, not to mention the legal

fees, since the response to their request for disclosure can only be as quoted above.

More of the same

Let's deal with a little more of the blatant before we turn to the subtle, shall we?

Most

informed readers are by now familiar with the 'Plea Bargain' myth; the offer that Kate claims to have been made 'indirectly,'

despite its being a feature of U.S. legal proceedings not permissible under Portuguese law, nor the 'life sentence'

a penalty recognised by Portuguese statute. Kate's indignation at such a tactic is amply covered on p. 243. Are we seriously

to believe that Kate McCann was such a V.I.P. that time-served police, family men themselves, would collectively sacrifice

their careers and their pensions just to 'cut her a deal?' She's clearly spent too much time in front of the television.

And only a grossly over-inflated ego could arrive at the conclusion that there would be a riot in the streets of England owing

to their being viewed as suspects in relation to a crime abroad. The next thing you know the British navy would be sending

a gunboat to the Arade river!

An entire chapter (21, Closing The Case) is devoted to convincing readers that the

investigation is history, with repeated reference to 'closure' and 'conclusion' on p.317.

Eventually

we read:

"On 24 July 2008, three days after the inquiry was closed..." (p.320).

Three years

later and no one seems to have told Leicestershire Constabulary. Strange that.

A number of Kate's little contradictions

are rather less easy to spot, as she cunningly exploits the transient nature of Short Term Memory, separating details of relevance

to each other by several paragraphs, pages - chapters even. It's a device she employs repeatedly. Nevertheless, despite

the apparent success of her overall routine, not all of her 'one-liners' are flawlessly delivered.

"Gerry

left to do the first check just before 9.05 by his watch...Madeleine was lying there, on her left-hand side, her legs under

the covers, in exactly the same position as we'd left her." (p.70).

(GM statement to police 10 May,

2007: 'Concerning the bed where his daughter was on the night she disappeared, he says that she slept uncovered,

as usual when it was hot, with the bedclothes folded down').

"The children were fast asleep and being

checked every thirty minutes...We were going into the apartments and looking as well as listening." (p.54).

(GM: "Yeah, I mean, I was saying this earlier, that at no point, other than that night, did I go stick my

head in. That was the only time..." [from the McCann inspired documentary, Madeleine Was Here]. MO [rogatory

interview]: "So I approached the room but I didn't actually go in because you could see the twins in the cots..."

And Madeleine?).

"As soon as it was light Gerry and I resumed our search." (p.83).

Resuming

something you have yet to start is a bit of a non sequitur if you ask me. How did the interview go again? Something

about 'not physically searching, but working really hard really?'

"Back in the apartment the cold

black night enveloped us all for what seemed like an eternity. Dianne and I sat there just staring at each other, still

as statues." (p.81).

That's hard work alright.

Passing the buck

Ambassador

John Buck receives a mention in despatches (several mentions actually), yet we're not concerned here with his passing

through, although there is something to be read into Kate's passing Goncalo Amaral on the stairs of the Lisbon courthouse,

which we'll come to later. Here we feature examples of the more colloquial meaning of the phrase.

Kate has

some advice for anyone in a similarly 'sticky situation' to her own:

"A word of advice in case you

are ever unlucky enough to find yourself involved in a criminal investigation in any country: always make sure that

you read your statement, in your own language, after you've provided it." (p.126).

This counsel clearly

has its origins in an unfortunate experience the author describes in some detail later. Her homily is also designed to give

the impression that she neglected to take, or was perhaps even denied, the opportunity of verifying her own statement(s) at

the time. She knows 'only too well,' from interviews with the PJ, how "words and meanings could get lost in translation..."

(p.333):

"At one point early on, something was read out from my initial statement, given on 4 May. It wasn't

quite accurate and I explained to the officer that the original meaning seemed to have been lost slightly in translation.

"To my astonishment, the interpreter became quite angry and suddenly interrupted. 'What are you saying? That

we interpreters can't do our job? The interpreter will only have translated what you told her!' I was staggered. Quite

apart from the fact that in this instance she was wrong - this definitely wasn't what I said - surely an interpreter is

there to interpret, not to interfere in the process? My trust in her took a dive." (p.239).

Turning the page,

however, we read of a certain procedural 'rigmarole' with which Kate is also familiar:

"It was 12.40

a.m. by the time the interview - and the attendant rigmarole of having it translated into Portuguese and then read back to

me in English by the interpreter - was over." (p.240).

Throughout the case files one encounters records of

witness statements, including those made by Kate and Gerry McCann, which conclude with the observation: 'Reads, confirms,

ratifies and signs.' Kate McCann does not speak Portuguese. Obviously, therefore, she will have 'read her own statement

in her own language after she'd provided it,' giving her the necessary insurance against any factual errors arising

from mis-translation, the likelihood of which was, in any case, remote in the extreme. Hence the indignation of the interpreter

on behalf of her maligned colleague.

A 'change of tune' neither implies nor derives from a mistaken interpretation

of the original melody necessarily. Kate is attempting here to shoot the piano player when only the composer is to blame.

But Kate McCann, presumably on the advice of her editorial committee, can let no opportunity for misinterpretation

pass her by it seems. Here's how she deals with the Smith sighting (p.98):

"Although, like Jane, this

family (the Smiths) had taken this man and child for father and daughter, they commented that the man didn't look comfortable

carrying the child, as if he wasn't used to it."

This is simply not true. The Smith family as

a whole made no such comment, and the interpretation of it to imply that 'discomfort' demonstrated the man was not

accustomed to carrying children (as a parent, say), is Kate's entirely. In point of fact, Aoife Smith (the Smith's

daughter), states: 'The individual's gait was normal. He did not look tired and walked normally while carrying the

child.' What Kate has done here is to deliberately over-interpret an observation made by Martin Smith, and Martin Smith

alone, as part of his witness statement to police, given on 26 May 2007:

"He adds that he did not hold the

child in a comfortable position."

It is the child who was seen to be uncomfortable not the carrier.

No inference was or should be made concerning the adult's experience of carrying children, although non-parental status,

were it to be established, would clearly rule out Gerry McCann (father to three children) as a 'possible' for inclusion

among candidate suspects.

I said she was subtle. She's also read the files 'in microscopic detail.'

Kate McCann would probably wish to argue that some of these instances are really no more than teeny-weeny white lies,

much as the McCanns' recruitment of private investigators Metodo 3 to operate inside Portugal was only 'technically

illegal.' But such things are not to be considered on a sliding scale from one to ten. Child abduction is a serious crime,

not a parlour game. In such a context there is no justification for putatively innocent parties to lie - at all.

However, we have tasted enough lies for the time being. Let's now sample some hypocrisy instead.

Do's

and don'ts

"Dave asked if we should get the media involved to increase awareness and recruit

more help. The reply was swift and unambiguous. 'No media! No media!’" (p.78).

"Dave, ... sent an e-mail to Sky News alerting them to the abduction of our daughter. (p.79).

"...Rachael had contacted a friend of hers at the BBC seeking help and advice..." (p.80).

"Jon Corner...was circulating photographs and video footage of Madeleine to the police, Interpol

and broadcasting and newspaper news desks. This was in accordance with the standard advice of the National Center for

Missing and Exploited Children in the US, which advocates getting an image of a missing child into the public domain as soon

as possible." (p.86).

Of course by 4 May the troupe had all heard about NCMEC, an organisation whose advice

as to the desirability of circulating an image would have been immediately familiar and acceptable to the Portuguese,

who had already planned on doing so.

This degrading little episode of civil disobedience is supposed to reflect

an urgent concern for the missing child, but speaks more of the arrogance of the participants, who seem to have been remarkably

easily persuaded that little Madeleine would not turn up locally and quickly.

And there's more:

"We

flew out to Portugal on 10 December.

"Not sure how I feel about seeing Mr Amaral - for the first

time ever, I hasten to add! I know I'm not scared but that man has caused us so much upset and anger because of how

he treated my Beautiful Madeleine and the search to find her. He deserves to be miserable and feel fear." (p.341).

"During a break in proceedings, I was going down the big stone staircase to the ladies' as Goncalo Amaral

was coming up. Thoughts of what I ought to say or do to him flashed through my mind but I stayed strong and passed

him without comment, our shoulders briefly coming within a foot of each other." (p.343/4).

Aggressive, vindictive

thoughts on Kate's part when she and Goncalo Amaral have yet to meet. However:

"It is extraordinary that

he (GA) could have said and written so many awful things about a person he had never met." (p.342).

I'd

call that hypocrisy, wouldn't you? Just as I would these next examples:

"Other letter-writers took a warped

pleasure, it seemed, in going into lurid detail which I couldn't bring myself to repeat here (p.310) about what might

have happened to Madeleine 'because of you.'"

Lurid detail being reserved of course for page 129:

"Haltingly, I told him about the awful pictures that scrolled through my head of her body, her perfect little

genitals torn apart..."

Under a more family friendly certificate we have:

"...the press know

what her name is and yet to this day they insist on calling her Maddie or Maddy. I find it quite disrespectful." (p.349).

Perhaps then, Kate might at some time account for her own disrespect toward Madeleine's younger brother:

"For the rest of that day I would hear Seany wandering around the house." (p.270).

"Seany

arrived in the early hours of the morning and positioned himself towards the middle of our bed, with me and Gerry then squeezed

together on one side." (p.277).

9 May

"Seany is a big soft 'Mummy’s boy'

which is nice." (p.304).

"'Hand him to me and walk away. He'll be fine,' she said confidently.

I'm sure she was right, though it wasn't much fun having to watch my little Seany, all red faced, blotchy and

sobbing." (p.359).

You couldn't make it up. But Kate McCann clearly has. From resisting the urge to 'flee'

on 7 September 2007 to deciding a day later to 'get out as soon as possible,' leaving 'a day earlier than originally

planned.' (p.256):

"We would go the next day rather than leaving it until Monday. Then it was all hands

on deck to pack everything up and clear the villa. Michael volunteered to stay on for a couple of days to organize the cleaning,

hand back the keys and arrange for our remaining belongings to be shipped home by a removal company." (p.255).

So where does 'planning' feature in all this last minute activity?

For an accurate barometer of just

how seriously Kate McCann has taken the search for Madeleine, one need only explore the issue of 'help.'

"While the officers looked around, Gerry called his sister, Trisha. As difficult as it was to tell our family, we knew

we needed help from home, and quickly." (p.77).

"Everyone had felt helpless at home and had rushed out

to Portugal to take care of us and to do what they could to find Madeleine. When they arrived, to their dismay they felt just

as helpless - perhaps more so, having made the trip in the hope of achieving something only to discover it was not within

their power in Luz any more than it had been in the UK." (p.109).

So what form could 'help from home'

have taken? What could be expected of relatives abroad that the very parents of the missing child could not themselves deliver

in the immediate circumstances? And when this charabanc party on a fool's errand discover they have embarked on precisely

that, who is implied as being responsible? Not those who whipped up the frenzy, but the well-meaning pilgrims themselves.

Then we have the more individual cases:

"Emma Knights, Mark Warner customer-care manager... tried

her best to comfort me, but my grief was so agonizing and personal that I wasn't sure whether I wanted her there or not.

I didn't really want anyone around me but people I knew well." (p.75).

"A lady called Silvia,

who worked at the Ocean Club, arrived to help out with translation... She was very kind and I was glad of her help and

support." (p.76).

"A middle-aged British lady ... announced that she was, or had been, a social worker

or child protection officer ... showing me her professional papers, including, I think, her Criminal Records Bureau Certificate.

She ... wanted me to go through everything that had happened the previous night. She was quite pushy and her manner, her

very presence, were making me feel uncomfortable and adding to my distress." (p.87).

"On the

way I rang a colleague - another lady of strong faith. She prayed over the phone for most of the trip, while I listened and

wept at the other end. I will forever be indebted to her for her help and support at that agonizing time." (p.88).

The pattern is simple and easy to interpret. Those in a position of some authority, with accreditation as regards

their professional competence, are given short shrift. Others with a well-meaning but largely amateur slant on the affair

are warmly embraced.

There is of course more that could be said - much more. But it wouldn't do to serve it

all up in an instant. Gerry's dismissal of the sniffer dog video as 'the most subjective piece of intelligence gathering

imaginable' (p.253) is but one such subject - a topic for discussion in its own right. One day soon perhaps we can do

more objectivity, just for Gerry. Until then, and paraphrasing that familiar remark by a judicious teacher, while we may not

have 'taught the McCanns all they know,' nor have we taught them all we know.

Fundamentally, there

are two elementary questions concerning the disappearance of Madeleine McCann which remain unanswered; a basic compound to

which Kate McCann has blithely added further ingredients:

1. Why should a couple directly related to the victim

of a serious crime, and in no small measure victims themselves therefore, lie about their own actions around the time the

crime was supposedly committed?

2. Why should others, not related to this victim of serious crime, lie

about what they were doing before the crime was apparently committed?

'Madeleine,' by Kate McCann,

does nothing to dilute the toxicity of this simple synthesis.

|

Mother's despair over child's

disappearance, 25 June 2011

|

|

Sat, 25 Jun 2011

The anguish of a mother whose young daughter, Madeleine, went missing on May 3, 2007, is reflected in most pages of

the book Kate McCann has written about her adored child.

Many readers, like me, may consider that McCann has packed

far too much detail in her heart-rending account of Madeleine's disappearance from a ground-floor holiday apartment bedroom

in Praia da Luz, Portugal, and the subsequent publicity that resulted in the girl's abduction receiving world-wide attention

for months on end.

But if McCann's book is suffused with a mother's despair and emotion, that is understandable.

Certainly, she is to be commended for an ability to communicate that many seasoned writers could well envy.

The

tragedy of Madeleine's abduction received wall-to-wall media coverage throughout the world.

Much of it was

the stuff of journalistic fiction, as well as accusatory comment.

Madeleine, almost 4, was on holiday with her

English GP mother, Kate, cardiologist father, Gerry, and younger twin brother and sister, Sean and Amelie.

On the

night of her disappearance, the children had been put to bed.

McCann and her husband were at a restaurant "only

30 to 45 seconds away". Their apartment was "largely visible" from the restaurant.

Gerry made the

first check of the apartment just before 9.05pm; Kate the second check at 10pm (after a dinner companion went to the apartment

30 minutes earlier and reported "all quiet!"), to discover that Madeleine was gone. Jane Tanner, a member of the

McCanns' holiday group, reported that about 9.15pm she saw a man in the vicinity carrying a child who appeared to be asleep.

On May 9, a Norwegian woman, Mari Olli, had seen a little girl who looked like Madeleine at a petrol station on the

outskirts of Marrakesh. She heard the blonde child of about 4, who looked pale and tired, ask the man in English, "Can

we see Mummy soon?", to which he replied, "soon". It wasn't until Olli and her husband were back at their

home on the Costa del Sol the next evening that they learned of Madeleine's disappearance.

One hundred days

later, McCann and her husband were under suspicion by the Portuguese police, an inferior and investigatively slow-moving lot,

who suggested Madeleine had been murdered. Much worse was to follow as the Portuguese police pressed on relentlessly in their

endeavours to fix responsibility on the English couple. Eventually, the pair were deemed to be innocent of wrongdoing.

Lurid newspaper stories about their lifestyle were churned out and a continuing series of supposed revelatory scoops

became the norm.

Both the Daily Express and the Daily Star acknowledged three stories were untrue,

and paid 550,000 into Madeleine's Fund that enables the couple to continue the search for their daughter. The royalties

from sales of this book will be given to the fund.

McCann, a woman of strong Catholic faith, kept a diary which

enabled her to produce a book that lacks no detail.

Judicious editing of her too repetitive bursts of emotion would

have profited the reader, without detracting from the sadness of a continuing family tragedy.

The book includes

many colour photographs and, commendably, an excellent index.

• Clarke Isaacs is a former chief

of staff of the Otago Daily Times.

|

Madeleine by Kate McCann, 30 June 2011 |

Madeleine by Kate McCann RTÉ

Taragh Loughrey-Grant

Thursday 30 June 2011

Madeleine may be one of the most heartbreaking books you will ever

read, telling as it does the haunting, true story of the disappearance of the pre-schooler days before her fourth birthday.

Written by her mother, Kate, it painstakingly retraces the family life of the McCann's, husband Gerry and their

three children, before and after tragedy struck when Madeleine went missing in 2007 while on holiday in Portugal.

The media coverage of the story was unprecedented but this book ends speculation over the thoughts, actions and reactions

of those who knew her best. There is no happy ending - the story gets darker with the turning of every page - but it is impossible

to walk away from this honest account unchanged. It sparks a need to know the truth.

Kate's prayers that the

book will help the Madeleine Fund have been answered as not only do all proceeds go towards the campaign but UK Prime

Minister David Cameron recently launched a new police investigation into the case.

|

Madeleine by Kate McCann -

II, 30 June 2011

|

|

Madeleine by Kate McCann - II

By John Blacksmith

Thursday, 30

June 2011 at 12:43

Madeleine as a primary source & historical record

As a celebrity memoir the book is by no means bad. What about as a record for future students of the case by one of the

two central figures? How reliable is it?

Here "the case" that we're discussing essentially concerns

May 3 and the week leading up to it. To a lesser extent it means the police investigation and that limited part of it for

which the McCanns are primary sources. The remainder of the book, the greater part in fact, is of little importance: people

studying the case, professional or otherwise, are unlikely to be deeply interested in the couple's extended travels around

Europe or the enlistment of celebrities such as David Beckham to their cause. In this section we shall look closely at the

first period and analyse it in detail; we can consider the couple's experiences at the hands of the Portuguese police

later on in the third part of this review, where we discuss the value of the book as a self-portrait of Kate McCann.

The constraints — the Portuguese judicial secrecy rules — which prevented her speaking in as much detail as

she apparently wished about the case no longer apply. The possibility (of which the couple were highly aware) that they might

lose their younger children to UK social services on the grounds of parental neglect perhaps justified a certain caution in

their accounts of events; with the passage of time, however, the likelihood of any such action has dropped to zero. And, finally,

M/S McCann now feels strong enough to confront those early days in Praia da Luz and has a fierce wish to write about events

and correct the "half-truths, speculation and full-blown lies appearing in the media and on the internet". As she

writes in the foreword to her book:

"...I have struggled to keep myself together and to understand how such

injustices [the half-truths etc above] have been allowed to go unchallenged over and over again. I have had to keep

saying to myself: I know the truth, we know the truth and God knows the truth. And one day, the truth will out."

So her day has come.

Construction

How has she tackled that week and what does she

have to tell us?

The first point to note is the extreme brevity of her coverage of the period. Out of the 368 pages

of the work some 27 are devoted to the week of the disappearance, culminating in her 10PM visit to apartment 5A — pages

44 to 71. Two of these are diagrams, leaving just 25 pages of text or some 7.5% of the work.

The structure of the

section is as follows:

1) A day to day account of the minutiae of the holiday, reading rather like an appointments

diary. Much of this indeed appears to be taken from a journal which she started keeping after May 2007 to assist her recollections.

Examination shows that this has been filled out by material taken from her statements to the Portuguese police and information

provided by the rest of the group in their 2008 statements to Leicester police, the so-called rogatory interviews. Finally

she has added brief titbits of an unimportant nature presumably taken once more from her journal — page 58, Gerry

buys a new pair of sunglasses, page 56, a fun game called "object tennis". Page 60, her pink running

shoes, would she be taken seriously wearing such a colour?

2) This takes up around 18 pages. The remaining

7 consist of insertions into the narrative — about a page and a half or so of complex memories of Madeleine and some

5 pages of justification by Kate for her actions written from outside the story itself.

When we look at the section

as a whole the main impression is the acute contrast between what has come before — the cheerful tale of her previous

life — and what follows — the emotion-filled drama of the investigation and the way in which it turned on them,

followed by the proud recitation of her achievements as a campaigner.

It stands alone, a flat recitation varied

only by the insertions. Incidents may indeed be described as "exciting" or "fun" but the words have no

resonance, being neither fun-filled nor in any sense exciting but all written in a monotone. Every writer, amateur or professional,

puts a part of themselves into a story whether they wish to or not, independent of the words they use: in Kate McCann's

case there is what we call an extreme disjunction between the words on the page and the real feelings of the author —

such as they are — as expressed in that mystery, the tone of a piece of writing.

Apart from the insertions

it is more of a drone than a tone. No interest in describing the period, or the wish to communicate the nature of the experience,

is anywhere discernible. Neither the appearance nor any hint of the personalities of the seven friends who accompanied her

to Praia da Luz are delineated: all of them, including the distinctively older Dianne Webster, remain mere names, their appearance

on the page just patches of black, or rather grey, type, carrying as much life or personal response from the author as a telephone

directory.

Now, from the rogatory interviews we know that the old newspaper picture of a secretive, homogenous

group was false. One or two of them were as near to close friends as the McCanns are ever likely to have; others hardly knew

the pair. In their own lengthy descriptions of that week, despite the fraught circumstances under which they spoke, their

personalities come to life – the owl-like and pompous but comically accident-prone David Payne, for example, his silkily

ambitious wife (the one with the scarves) whose perfume can almost be smelt on the page, the embittered and hostile Russell

O'Brien, deep-down conscious that his carefully planned career will never be the same again, the stage-comedy scatty old

lady Dianne Webster, who can't even remember her own address and isn't old at all, veering wildly between genuine

forgetfulness and a sharp suspicion that the less she says about anything the better for everybody.

And their descriptions

are alive as well, full of unexpected detail, doubt, colour, disappointment, incident and emotion, giving the lie to any suggestion

that there really wasn't much for Kate McCann to write about in that Praia da Luz week. Unlike her the 7 — except,

of course, when they stray into certain "dangerous" areas — tell things more or less as they saw and, more

important, felt them.

Can we be sure that the section has in fact been structured in the way we have described?

Well, the passages of self-justification are obviously ex post facto, as they say, and therefore cannot have come

from the period; nor have they in any sense sprung from the narrative of that week since they have nothing to do with communicating

what happened then but are part of a quite different story, M/S McCann's continuing defence of her own reputation, the

"bottom of the garden" stuff and the rest in which she first lightly condemns and then strongly acquits herself.

Then what about the Madeleine passages? Can we be fairly sure that they don't spring from the narrative either?

They certainly don't seem to. Significantly our first real view of Madeleine on holiday — on the aircraft steps

— is given not from direct memory but from the video made by the group. A few pages after that the bare recitation

of events and lengthy descriptions of the apartment is interrupted:

"Soon after midday," she writes,

"we collected the children." A highly emotional passage about the child follows — but it doesn't describe

Madeleine McCann in Praia da Luz but in some more complex space: "I loved going to pick up the kids when they were little,"

she adds, "the moment when your child spots you and rushes over to throw a pair of tiny arms around you makes your heart

sing. It doesn't happen every time, of course, but I have many special memories of meeting Madeleine at nursery at home.

Hurtling across the classroom and into my embrace she would shout, 'My mummy!," as if establishing ownership

of me in front of the other children. What I'd give to have that back again."

The next is on page 57:

"It chokes me remembering how my heart soared with pride in Madeleine that morning. She was so happy and obviously

enjoying herself. Standing there listening intently to Cat's instructions, she looked so gorgeous in her little T-shirt

and shorts, pink hat, ankle socks and new holiday sandals..." OK, OK — but this wasn't strictly the child in

Praia da Luz either, but a photograph:

"... that I ran back to the apartment for my camera to record

the occasion." The child herself is momentarily excluded as Kate McCann shifts time and space once more, "One of

my photographs is known around the world now..." and in a convoluted mix of past and present, child and parent, tells

us how it was that Madeleine had "done really well" to end up for the photograph with an armful of tennis balls,

finishing, "Gerry loves that picture."

On page 65 she demonstrates how hard she finds it to "see"

the child, providing not an image of Madeleine in action but a multi-layered section of her own troubled memory from somewhere

far beyond Praia da Luz:

"Some images are etched for all time on my brain. Madeleine that lunchtime is one

of them. She was wearing an outfit" — here comes mum — "I'd bought especially for her holiday:

a peach-coloured smock top from Gap and some white broderie-anglaise shorts from Monsoon — a small extravagance perhaps,

but I'd pictured how lovely she would look in them and I'd been right." She adds, "She was striding

ahead of Fiona and me, swinging her bare arms to and fro. The weather was on the cool side" — here she is again

— "and I remember thinking I should have brought a cardigan for her, although she seemed oblivious of

the temperature, just happy and carefree" — again — "I was following her with my eyes, admiring

her. I wonder now, the nausea rising in my throat, if someone else was doing the same."

Her characterization

of the child throughout these interpolations is flimsy and as for the dynamics of the relationship between mother and daughter

— and anyone with children of Madeleine's age knows how extensive and complex the relationship has already become

— there is almost nothing.

I stress these points not at all to criticise Kate McCann as a mother but to illustrate

the way in which the child does not emerge naturally from the narrative — and that is because she is not really part

of it. Perhaps the closest she comes to emerging is in the descriptions of her asking her parents "why they hadn't

come that night" — and that episode also, in a sense, comes from outside, due to the evidential significance it

has subsequently taken on.

From these considerations it should be clear that the whole section results neither

from concentrated recollection nor the intensity of her feelings about episodes of four years ago: it has been assembled into

a construct, not a description and certainly not a record. Of course every piece of writing of whatever kind is a

construction, a literary construction, if only by selection. But a literary construction is chosen for its suitability to

express the story, whether fact or fiction, in the best or most appropriate way. This section of Kate McCann's book is

something quite different: tellingly, she never "expresses herself" at all.

The only interpretations

of this extraordinary section that seem to make sense are, firstly, those that are probably familiar to her criminal lawyers:

that she suffered from traumatic amnesia that week as a result of losing her child or for some pre-existing reason and has

had to reconstruct the period from outside sources; or that she is still incapable, despite her own assumptions, of truly

confronting the events of the period.

There is, of course, a third: that she sees that whole week as a potentially

"dangerous area" a shark filled sea in which she must move with enormous caution, her only safe refuges the island

of ex post facto justification and the haven of her undoubted love for Madeleine, however strangely revisited.

Can

we go further and decide which of the three might be correct? One way of doing so is to remember those opening words:

"...I have struggled to keep myself together and to understand how such injustices [the half-truths etc above]

have been allowed to go unchallenged over and over again. I have had to keep saying to myself: I know the truth, we know the

truth and God knows the truth. And one day, the truth will out."

"Dangerous" or merely "contentious"?

Either way, how Kate McCann handles areas of the case which have provoked so much comment and debate, and how much light her

quest for truth will throw on them can help us decide which interpretation fits best.

Leaving aside the whole question

of the state of the apartment at 10PM on May 3, a subject about which by now we can be fairly sure M/S McCann is not going

to have anything new to say, these contentious areas come down to three episodes: the decision not to use babysitters, the

supposed visit of David Payne to her apartment on the early evening of May 3 and the notorious problems of the evening "timeline."

The Babysitting Decision

The decision prompts a number of questions that in theory, and

for a person who has nothing to hide, should be easy enough to answer: who exactly first suggested that the group should check

the children and when? What stance did Gerry McCann, a born contributor, take? What was agreed about checking other couples'

children and what arrangements, keys, open doors etc, were agreed within the group to allow others entry to their apartments?

And did they discuss or assess the risks of such a procedure before coming to a decision?

Dr Payne being

ingenious in his rogatory interview

In the rogatory interviews the matter was

treated as "dangerous ground". The group gave vague and contradictory answers to some of the questions but stood

firm in claiming that the decision to check their children had been a "collective" one. Their responses, taken together

with their police statements, demonstrated that there had been an attempt to construct a strong legal case against any charges

of neglect arising from the checking after the child had disappeared.

That case, developed and made explicit to

the police by David Payne, was superficially ingenious: Mark Warner, it ran, used "listening checks" at most of

its resorts with staff listening at guests' windows every half an hour for signs of wakefulness or distress; finding that

Mark Warner did not use the system in Praia da Luz the group put in place a system that followed the company's half-hour

intervals; in fact, said Payne and others, apparently with straight faces, it was better than Mark Warner's system

because there was some visual checking inside the apartments as well; therefore they could only be guilty of neglect if Mark

Warner was prosecuted for the same offence in all its resorts.

Of course there were all sorts of problems with

this claim, not least that it sounded strongly like our old friend ex post facto preparation and reeked of urgent legal discussion

after the disappearance of the child, not before. And it was all too neat, especially when the four members of the group who

had absurdly claimed that the checking was every fifteen minutes — some whir of motion in the Tapas restaurant that

would have been — in their May 4 statements began shading their claims towards the half-hour mark. Still, it was hard

to disprove unless the police could find out whether such elaborate and conscientious planning had really taken place at the

beginning of the holiday rather than afterwards. All nine in the group, however, refused or transparently affected not to

remember who said what and when, repeating only that it was a "collective decision".

But why should the

police, Portuguese or UK, be so concerned about possible neglect as to try and break down their story in view of the appalling

disaster that the group had suffered? Did it really matter enough for the Leicester police still to be trying to find out

the background to the decision in April 2008?

The answer is no, it didn't. What mattered — and here the

size of the pit the Tapas 7 (not the 9) were digging for themselves begins to come clear — was something much more important:

the group was clearly not telling the whole truth but was that simply to evade the dreaded neglect issue? If they weren't

willing to come completely clean on that, even a year later, just how honest were they and could they be concealing something

much more sinister?

That question, with all its implications, remains open and unanswered to this day,

prompting much debate on the internet and, no doubt, a number of open files in Leicester police headquarters. It is extremely

thought-provoking — and here we see the size of that pit again — that apparently not one of the Tapas 7 has come

forward after four years and said, in effect, to the UK police, "Look, we were troubled; of course the 'collective

decision' thing was a stance but an understandable, not a sinister, one. Can't we start again and clear this up?"

Of course it is possible that one of them has done so; if so he hasn't told Kate McCann. Her contribution to dismissing

baseless rumours in this section of Madeleine might sound slightly familiar:

"As the restaurant was

so near we collectively decided to do our own child checking service" — followed, without further detail,

by an entire page of prolix and defensive self-justification, again familiar from her previous media interviews.

The David Payne Visit — Multiple Worlds?

The visit, the "last sighting" of Madeleine

McCann by someone outside the family, remains highly controversial and has been the subject of exhaustive debate on the internet

and elsewhere.

The questions about it arise at the very beginning since it was not mentioned by David Payne, Gerry

or Kate McCann in their initial police statements, despite Kate McCann's repeated assertions in the book that she had

told the police "everything". The first reference to it comes, oddly, not from either of the individuals involved

but from Gerry McCann, in his May 10 statement:

"David went to visit Kate and the children and returned close

to 19H00, trying to convince the deponent to continue to play tennis, which he refused."

Note the initial

locution, "David went to visit Kate and the children": there is no mention of any reason for the visit. Unfortunately

the PJ did not hear what the principals had to say: neither Payne nor Kate McCann were present for that second round of interviews.

Kate had cried off with stress; quite how Payne avoided questioning is unclear. Whatever, the result was that the Portuguese

police received no information about the claimed visit from one of the participants until Kate McCann was questioned over

four months later, on September 6 2007. And they still had no statement from Payne; in fact they were unable to compare his

account with that of Kate McCann until they listened in to his rogatory interview in April 2008.

Kate McCann's

September 6 statement runs thus:

"While the children were eating and looking at some books, Kate had a shower

which lasted around 5 minutes. After showering, at around 6:30/6:40 p.m. and while she was getting dry, she heard somebody

knocking at the balcony door. She wrapped herself in a towel and went to see who was at the balcony door. This door was closed

but not locked as Gerry had left through this door. She saw that it was David Payne, because he called out and had opened

the door slightly."

She now departs from direct knowledge deriving from her own experience, as she often does

on important matters, adding helpfully:

"David's visit was to help her to take the children to the recreation

area. When David returned from the beach he was with Gerry at the tennis courts, and it was Gerry who asked him to help Kate

with taking the children to the recreation area, which had been arranged but did not take place."

Then, reverting

from hearsay to evidence, she concluded:

"David was at the apartment for around 30 seconds, he didn't

even actually enter the flat, he remained at the balcony door. According to her he then left for the tennis courts where Gerry

was. The time was around 6:30-6:40PM."

This was the first appearance of the "Gerry asked Payne..."

story — after four months! — and it was followed some twenty four hours later by the same story from Gerry himself

in his arguido interview.

Two weeks later, with the couple safely back in England and during that muffled and murky

period when they and the lawyers were using the media to explore their vulnerabilities, a lengthy and carefully contrived

leak was given to the London Times by Clarence Mitchell. The story purported to be about disagreements between the

McCanns as to how far to co-operate with the PJ but buried half way into the story we find this:

"Last week,

however, a senior police source told a Portuguese newspaper that officers were still suspicious about the McCanns' movements

during the "missing six hours" before Madeleine's disappearance.

Sources close to the family [Clarence

Mitchell] say that David Payne, one of the holiday party, saw Madeleine being put to bed when he visited the McCann apartment

at 7PM. Previously the last confirmed sighting of Madeleine was at 2.29PM when a photograph of her and Gerry was taken at

the swimming pool.

Kate and Gerry McCann believe Payne's testimony will be crucial in proving their innocence.

They arrived at the tapas bar at 8.30PM, which would leave just an hour and a half in which they are supposed to have killed

their daughter and disposed of the body.

A source close to the legal team [this was also Mitchell] said:

'If they were responsible for killing their daughter, how would they have done so and hidden the body in that time? There

is a very limited window of opportunity.'"

So the story had developed even further. Note that Payne himself,

after almost six months, has still told the Portuguese police absolutely nothing about the visit. The only reference to it

that he ever seems to have made comes in a curiously unsatisfactory email from the Leicester police to their Portuguese counterparts

accompanying some forwarded statements. Detective Constable Marshall wrote that Payne had stated informally:

"...that

he saw Madeleine, for the last time, at 17H00 [probably an error for 7PM] on 3/5/07 in the McCann apartment. Also

present there were Kate and Gerry. He did not indicate the motive for being there or what he was doing. He also cannot indicate

how long he stayed."

Well!

The situation, therefore, was that Payne's version of this

visit was still open and, as it were, up for grabs. But not yet and certainly not for grabbing via the newspapers by the McCanns

and their spokesman. As we have seen from his ingenious defence of the "checking" Payne has an instinct for keeping

his options open. The claims were left standing, without rebuttal, for several weeks and perhaps there was a hope somewhere

that it reflected Payne's acquiescence in the story and the altered timescale. Not likely.

In late October,

strangely enough on the same date that Detective Constable Marshall sent his email along with the Gaspar statements to Portugal,

he made the extremely rare move of communicating via journalists himself, speaking effusively to the Daily Mail about

Kate McCann and her lack of problems with her children [media code: no, she wasn't nutty or stressed-out enough to

have whacked the child and accidentally killed her]. But 7PM was now firmly out: in that same article Mitchell and the

McCanns had to reverse themselves, now stating "David Payne saw Madeleine at around 6.30pm." Point made.

In April 2008, just under a year after the child's disappearance, David Payne was finally compelled to talk about

the visit, making a statement to Leicester police as part of the rogatory interviews. The Portuguese police representatives

watched the televised proceedings from behind a screen. Whether Lusitanian guffaws of disbelief resounded from their vantage

point is not disclosed but Payne and Kate McCann seemed to be not just on different visits but different planets.

Q: Okay, and it was at what point that Gerry said to you go and, would you mind checking at Kate?

DP:

I had to go back to my room to you know change into stuff appropriate for playing tennis in, and err so he knew that I'd

walk up that by and past so he said oh why don't you err, you know can you just pop in on the way, the way up...[fails

to describe reason for visit]

KM again: David's visit was to help her to take the

children to the recreation area. When David returned from the beach he was with Gerry at the tennis courts, and it was Gerry

who asked him to help Kate with taking the children to the recreation area,

Q: Did you open the door?

Or was it already open?

DP: I think it was already open.

KM: This door

was closed but not locked as Gerry had left through this door. She saw that it was David Payne, because he

called out and had opened the door slightly.

Q: Did you actually go into the apartment?

DP: I did.

Q: Or did you do the conversation from the door?

DP: No, definitely was inside

the apartment, you know whether it be two or three steps into the apartment or you know however many, but I was definitely

in the apartment.

KM: He didn't even actually enter the flat; he remained at the balcony

door.

Q: Okay, so now what I'm gonna try and ask you to recollect, what everybody

was wearing.

DP: I'm afraid that is, you know I'm, I cannot recall at all. I know that's, you'd

think that'd be an obvious thing to remember, I cannot remember. As I say the, from the children point of view predominantly

I can remember the, you know, white, but I couldn't say exactly what they were wearing. Err…

Q: But

could you remember what Kate was wearing for example?

DP: I can't, no.

KM:

She wrapped herself in a towel and went to see who was at the balcony door.

Q: I'm gonna

pin you down and ask you how long you think you were in there for.

DP: In their apartment, it, it, I'd

say three minutes, five maximum.

KM: David was at the apartment for around 30 seconds.

Q: When you finished ...did you say anything to Gerry about, about the fact that his family were fine?

DP: Yeah, err yeah, I haven't mentioned this before, but yes, yeah I'd certainly, when we met up I said oh

yeah, you know everything's fine there, you know probably along the lines of you know you've got a bit more of a free

pass you know you can carry on for a bit longer...[fails to give reason for visit]

KM: ...asked him to

help Kate with taking the children to the recreation area.

What can one say? It doesn't corroborate

and it doesn't tally: there might have been visits to apartment 5A by David Payne or other members of the group that day

but the written evidence shows that the one described by Payne and the McCanns did not take place.

Dangerous

waters! What does Kate have to say now? Very little. In the book she falls back on copying out her September 6 statement:

"At around six forty, as I was drying myself off, there was a knock on the patio doors and I heard David's

voice calling me. Swiftly wrapping my towel around me I stepped into the sitting room."

But then she uses

words that aren't in the statement: "David had popped his head round the patio doors looking for me," which

quite cleverly attempts to resolve the open/closed doors discrepancy as well as shading another question — inside the

doors or outside the doors? Neither! He is in the doorway, head popping.

Having dipped her toes she moves rapidly

back to the much safer territory of what others had said:

"The others had met up with Gerry at the tennis

courts and he'd mentioned we were thinking of bringing the kids to the play area. David had nipped up to see if he could

give me a hand taking them down. As they were all ready for bed and seemed content with their books I decided they were probably

past the stage of needing any more activity. So he went back to the tennis while I quickly dressed and sat down on the couch

with the children."

One wonders which lawyers were involved in the "popping" paragraph because,

by altering her statement, Kate McCann has provided internal evidence that she is covertly attempting to smooth away inconsistencies

that are hazardous for her rather than trying to throw light on the truth as she vowed to do. Oh, and the bit about Payne

only staying for thirty seconds has somehow gone missing.

Nine O'clock News

Finally

to the evening of May 3. M/S McCann is certainly not going to linger here and events before 10PM are despatched in a two page

deadpan recitation of her statement, beginning with, "Gerry left to do the first check just before 9.05 by his watch."

By his watch? So near the end and more pause for thought!

Gerry did not mention looking at his watch and

noting 9.04 until the desperate hours of his September arguido statement, and for very good reason: it couldn't be true.

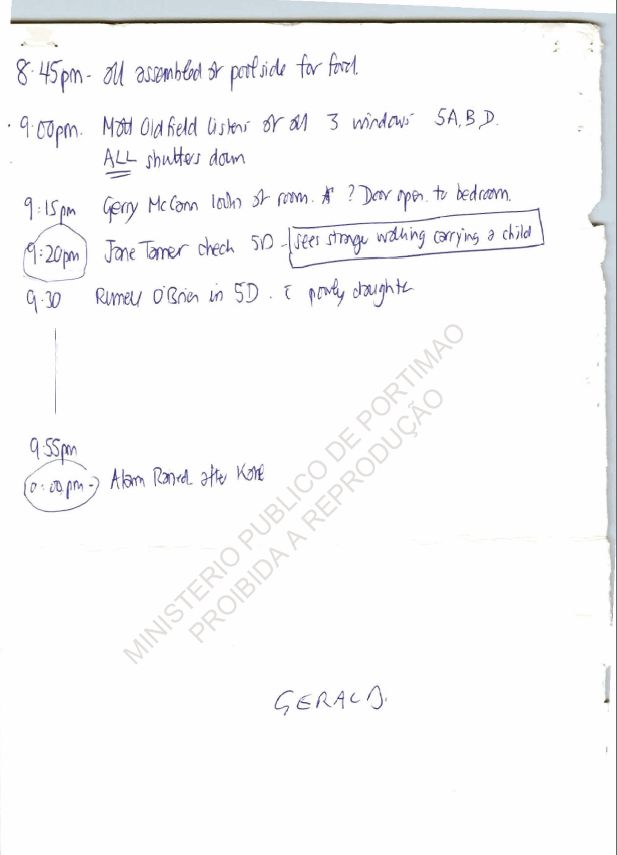

We know that he was actively involved in the preparation of the two "kid's book" timelines in apartment

5A on the night of May 3/4, a subject on which Kate is understandably silent. Not surprisingly the person who wrote these

timelines down, Russell O'Brien, was almost equally coy about their preparation when interviewed by Leicester police,

stating that he had forgotten their existence.

Nevertheless, under questioning, he began to remember and

confirmed not only his own role but that of David Payne and Gerry McCann in their preparation – while the searching

and hue and cry was taking place around them and all within a few feet of Kate. If Kate McCann, indeed, had happened to wonder

why one of Madeleine's books had been ripped apart and glanced down at the timelines written on their covers she would

have seen "9.20 Jane Tanner checks 5D, sees a stranger carrying a child." Apparently she didn't, not finding

out about the sighting, so we are told, until very much later.

So where's

9.04?

O'Brien was vague and inconclusive about the exact role that each of

the three played in their preparation but nevertheless it was established that Gerry McCann had been involved in both versions

and that the second — marked "Gerald" so he could hardly deny it — included amendments from him.

Not here either

The first sheet that the trio prepared states that Gerry left to check at "9.10 -9.15".

The second, corrected by Gerry, alters this to "9.15". There is no mention of 9.05, let alone 9.04. That the alteration

was part of a process in which almost all checking times were systematically shifted by five minutes or so to accommodate

the otherwise insoluble conflicts between Gerry McCann's presence in 5A and Jane Tanner's sighting directly outside,

does not concern us here. What matters is the internal evidence of the documents as to the truth: McCann could not possibly

have allowed either document to pass unamended if he had indeed looked at his watch at 9.04 as he left to check. The documents

show that the claim about the watch, first made four months after the event, is an invention.

And so we arrive

at Kate's 10 PM check, there to read the cold leftovers of her previous statements and interviews. With that the strained

and artificially constructed narrative of this section can come to an end, to be replaced immediately – and almost with

a sense of relief — by wild, fist-beating, screaming action.

This piece which purports to describe Madeleine's

last known week is a sadly unworthy memorial to a small and unfortunate child. As a historical record Kate McCann's

Madeleine is, as we have seen, self-serving and actively resistant to the truth. It is worthless.

|

Too many 'if onlys', 08 July

2011

|

|

08 Jul 2011

MADELEINE is the disquieting account of the disappearance and subsequent search for the British girl Madeleine McCann,

written by her mother Kate, and includes excerpts of the diary Kate kept over that harrowing period.

It's

a riveting personal account of the incident, which many of us have read much about in the years since Madeleine was snatched,

but at the same time, the enormity and horror of what happened to the gorgeous three-year-old, and what might have happened

to her subsequently, make it a harrowing read. Madeleine's happy wide-eyed photo on the cover is heart-wrenching.

It's hard not to make judgment calls on the parents, medical doctors Kate and Gerry, who while holidaying at a resort