Madeleine Case - A Pact of Silence, 30 June 2007 (Jeremy Wilkins

name made public for the first time)

|

Madeleine Case - A Pact of Silence SOL

By Felicia Cabrita and Margarida Davim

30 June 2007

Thanks to

Astro for translation

- Extract -

Only Jane saw the man carrying a child

But there is a witness whose deposition contradicts this

theory. Jeremy Wilkins - a TV producer who had met Maddie's father during their holidays and used to play tennis

with him - was walking his eight months old son at that time. He met Gerry, who went out through the apartment's back

door after having checked on the children, and the two men exchanged a brief conversation. At that time, if one is to believe

the first accounts, Jane would have left Tapas in the direction of the apartment's main entrance, and would have crossed

paths with both of them. "It was a very narrow road and I think it would have been almost impossible to walk by without

me taking notice", Jeremy says, pointing out the fact that he saw no man carrying a child, as Jane states.

But

Jane continues to guarantee that, at the top of the street, she saw a man with a child in his arms.

Although the

area is scarcely lit, and the situation did not make her suspicious at the time, she describes the beige trousers, the dark

thick jacket and the black classic-style shoes in a detailed way. Once again, Jeremy disagrees: "If that happened, I

would have likely seen it".

|

|

|

Maddie: The Secret Witness, 16 September 2007 |

Maddie: The Secret Witness News of the World (no longer available online)

TV boss holds vital clue to mystery

By Dominic Herbert & Ross Hall

16 September

2007

THIS is the secret witness whose bombshell testimony could clear the McCanns.

Pictured here for the first time, Jeremy Wilkins' evidence blows holes in the police theory that Gerry

and Kate killed four-year-old Madeleine.

Wilkins — seen outside his north west London

home — was the man heart surgeon Gerry McCann, 38, spoke with for up to 15 minutes outside the holiday apartments —

moments after checking on his children for the last time.

What the TV producer witnessed

makes the statement he gave to police a key piece of evidence in the event of a trial.

A

friend of Wilkins told the News of the World: "He is entirely convinced of Kate and Gerry's innocence. He believes

they are a decent family caught up in an unimaginable nightmare."

We can reveal Wilkins

constantly INSISTED to Portuguese detectives that Gerry was totally calm and unflustered as they chatted—far removed

from the behaviour that might be expected of a man covering up the death of his daughter.

But

another part of Wilkins' evidence ironically helped shift the police focus AWAY from their original kidnap theory.

For the 36-year-old holidaymaker turned the investigation on its head when he revealed a VITAL

FLAW in the statement given by key witness, Jane Tanner (right), who claims she saw a man carrying a child away from the apartment

complex.

Based on what he has said, Portuguese sources confirmed that police have doubts

about Miss Tanner's evidence.

One said: "Her account has raised more questions than

answers. She is high on the list of people we need to speak to again."

Wilkins was refusing

to expand on what he has told police. His girlfriend Bridget O'Donnell —who was in Praia da Luz with the producer

and their eight-month-old son—said: "We have decided it's not appropriate to talk about what happened."

Wilkins' pal added: "He came back from the holiday totally shell-shocked. He was part

of a British crowd which included the McCanns who became friends as they holidayed in Portugal.

"He played tennis with Gerry the day before Madeleine disappeared. He has barely said a word about the whole case.

He feels as a potential witness that would be inappropriate."

Wilkins—whose production

company Zig Zag has made a string of controversial TV programmes—is likely to be re-interviewed as Portuguese detectives

desperately try to build a case against the McCanns.

Some of the seven diners who were at

the tapas restaurant with the couple on May 3 have already travelled back to Portugal once before to go over events leading

to Madeleine's disappearance.

Next time they may be quizzed in the UK by British police assisting their EU

counterparts on the inquiry.

Wilkins' crucial encounter with Gerry took place at 9.10pm on the main street

outside the apartments next to the McCanns'—and at the entrance to a narrow alleyway that runs past the back of

them.

The two were both tennis fans and had played each other during the course of the holiday.

On the night Maddie disappeared Wilkins was taking his eight-month-old son for a walk.

When he bumped into Gerry the two men chatted for up to 15 minutes before the surgeon returned to the tapas

bar.

It was during this period of time that Tanner, 37, another member of the McCanns' party, said she WALKED

PAST the two men on her way back to her apartment to check on her youngsters.

She told police

that she saw a dark-haired man, aged about 35, carrying a child who could have been Maddie's wrapped in a blanket at 9.15pm—when

Gerry and Wilkins would still have been chatting.

But Wilkins, viewed by police as a completely

independent witness, told cops he could not recall anyone walking past him. And in all the time he was there he saw NO MAN

carrying a child.

The TV executive is convinced he would have seen Jane Tanner pass by.

He said: "It was a very narrow path and I think it would have been almost impossible for

anyone to walk by without me noticing."

And he also believes he would have seen the mystery man and child

who would also have been just yards away.

Cops asked mum-of-two Tanner—on the holiday

with with her partner Dr Russell O'Brien, 36—whether it was possible that the man and child she saw was Wilkins

with his son.

Check

But a source told us: "She was adamant that it was not Jeremy Wilkins and his child. She is certain she saw someone

else and stands by her account."

Gerry and Tanner returned to the restaurant separately

shortly afterwards and it was at 10pm that Kate McCann went to check on the children and found Madeleine gone.

Wilkins'

importance in the inquiry has only been highlighted because police are troubled by possible inconsistencies in the McCann

friends' statements, including discrepancies in the times various people recall arriving at the restaurant.

The Portuguese police believe the McCanns may have been involved in Madeleine's disappearance and think

one may be covering up for the other.

Officers are probing an unlikely "three-hour window

of opportunity" between 6pm and 9pm when they suspect Madeleine was killed in the apartment and her body hidden somewhere

nearby. Forensic evidence gathered so far including DNA or body fluid samples is thought to be inconclusive.

Portuguese police say they could name more official suspects in the coming weeks.

|

My months with Madeleine, 14 December 2007 |

My months with Madeleine The Guardian

It was a welcome spring break, a chance to relax at a child-friendly resort in

Portugal. Soon Bridget O'Donnell and her partner were making friends with another holidaying family while their three-year-old

daughters played together. But then Madeleine McCann went missing and everyone was sucked into a nightmare

Bridget O'Donnell

Friday December 14 2007

|

| Bridget O'Donnell. Photograph: Graeme Robertson |

We lay by the members-only pool staring at the sky. Round and round, the helicopters clacked and roared.

Their cameras pointed down at us, mocking the walled and gated enclave. Circles rippled out across the pool. It was the morning

after Madeleine went.

Six days earlier we had landed at Faro airport. The coach was full of people like us, parents

lugging multiple toddler/baby combinations. All of us had risen at dawn, rushed along motorways and hurtled across the sky

in search of the modern solution to our exhaustion - the Mark Warner kiddie club. I travelled with my partner Jes, our three-year-old

daughter, and our nine-month-old baby son. Praia da Luz was the nearest Mark Warner beach resort and this was the cheapest

week of the year - a bargain bucket trip, for a brief lie-down.

Excitedly, we were shown to our apartments. Ours

was on the fourth floor, overlooking a family and toddler pool, opposite a restaurant and bar called the Tapas. I worried

about the height of the balcony. Should we ask for one on the ground floor? Was I a paranoid parent? Should I make a fuss,

or just enjoy the view?

We could see the beach and a big blue sky. We went outside to explore.

We settled

in over the following days. There was a warm camaraderie among the parents, a shared happy weariness and deadpan banter. Our

children made friends in the kiddie club and at the drop-off, we would joke about the fact that there were 10 blonde three-year-old

girls in the group. They were bound to boss around the two boys.

The children went sailing and swimming, played

tennis and learned a dance routine for the end-of-week show. Each morning, our daughter ran ahead of us to get to the kiddie

club. She was having a wonderful time. Jes signed up for tennis lessons. I read a book. He made friends. I read another book.

The Mark Warner nannies brought the children to the Tapas restaurant to have tea at the end of each day. It was a

friendly gathering. The parents would stand and chat by the pool. We talked about the children, about what we did at home.

We were hopeful about a change in the weather. We eyed our children as they played. We didn't see anyone watching.

Some of the parents were in a larger group. Most of them worked for the NHS and had met many years before in Leicestershire.

Now they lived in different parts of the UK, and this holiday was their opportunity to catch up, to introduce their children,

to reunite. They booked a large table every night in the Tapas. We called them "the Doctors". Sometimes we would

sit out on our balcony and their laughter would float up around us. One man was the joker. He had a loud Glaswegian accent.

He was Gerry McCann. He played tennis with Jes.

One morning, I saw Gerry and his wife Kate on their balcony, chatting

to their friends on the path below. Privately I was glad we didn't get their apartment. It was on a corner by the road

and people could see in. They were exposed.

In the evenings, babysitting at the resort was a dilemma. "Sit-in"

babysitters were available but were expensive and in demand, and Mark Warner blurb advised us to book well in advance. The

other option was the babysitting service at the kiddie club, which was a 10-minute walk from the apartment. The children would

watch a cartoon together and then be put to bed. You would then wake them, carry them back and put them to bed again in the

apartment. After taking our children to dinner a couple of times, we decided on the Wednesday night to try the service at

the club.

We had booked a table for two at Tapas and were placed next to the Doctors' regular table. One by

one, they started to arrive. The men came first. Gerry McCann started chatting across to Jes about tennis. Gerry was outgoing,

a wisecracker, but considerate and kind, and he invited us to join them. We discussed the children. He told us they were leaving

theirs sleeping in the apartments. While they chatted on, I ruminated on the pros and cons of this. I admired them, in a way,

for not being paranoid parents, but I decided that our apartment was too far off even to contemplate it. Our baby was too

young and I would worry about them waking up.

My phone rang as our food arrived; our baby had woken up. I walked

the round trip to collect him from the kiddie club, then back to the restaurant. He kept crying and eventually we left our

meal unfinished and walked back again to the club to fetch our sleeping daughter. Jes carried her home in a blanket. The next

night we stayed in. It was Thursday, May 3.

Earlier that day there had been tennis lessons for the children, with

some of the parents watching proudly as their girls ran across the court chasing tennis balls. They took photos. Madeleine

must have been there, but I couldn't distinguish her from the others. They all looked the same - all blonde, all pink

and pretty.

Jes and Gerry were playing on the next court. Afterwards, we sat by the pool and Gerry and Kate talked

enthusiastically to the tennis coach about the following day's tournament. We watched them idly - they had a lot of time

for people, they listened. Then Gerry stood up and began showing Kate his new tennis stroke. She looked at him and smiled.

"You wouldn't be interested if I talked about my tennis like that," Jes said to me. We watched them some more.

Kate was calm, still, quietly beautiful; Gerry was confident, proud, silly, strong. She watched his boyish demonstration with

great seriousness and patience. That was the last time I saw them that day. Jes saw Gerry that night.

Our baby

would not sleep and at about 8.30pm, Jes took him out for a walk in the buggy to settle him. Gerry was on his way back from

checking on his children and the two men stopped to have a chat. They talked about daughters, fathers, families. Gerry was

relaxed and friendly. They discussed the babysitting dilemmas at the resort and Gerry said that he and Kate would have stayed

in too, if they had not been on holiday in a group. Jes returned to our apartment just before 9.30pm. We ate, drank wine,

watched a DVD and then went to bed. On the ground floor, a completely catastrophic event was taking place. On the fourth floor

of the next block, we were completely oblivious.

At 1am there was a frantic banging on our door. Jes got up to

answer. I stayed listening in the dark. I knew it was bad; it could only be bad. I heard male mumbling, then Jes's voice.

"You're joking?" he said. It wasn't the words, it was the tone that made me flinch. He came back in to the

room. "Gerry's daughter's been abducted," he said. "She ..." I jumped up and went to check our

children. They were there. We sat down. We got up again. Weirdly, I did the washing-up. We wondered what to do. Jes had asked

if they needed help searching and was told there was nothing he could do; she had been missing for three hours. Jes felt he

should go anyway, but I wanted him to stay with us. I was a coward, afraid to be alone with the children - and afraid to be

alone with my thoughts.

I once worked as a producer in the BBC crime unit. I directed many reconstructions and

spent my second pregnancy producing new investigations for Crimewatch. Detectives would call me daily, detailing their cases,

and some stories stay with me still, such as the ones about a girl being snatched from her bath, or her bike, or her garden

and then held in the passenger seat, or stuffed in the boot. There was always a vehicle, and the first few hours were crucial

to the outcome. Afterwards, they would be dumped naked in an alley, or at a petrol station with a £10 note to "get

a cab back to Mummy". They would be found within an hour or two. Sometimes.

From the balcony we could see

some figures scratching at the immense darkness with tiny torch lights. Police cars arrived and we thought that they would

take control. We lay on the bed but we could not sleep.

The next morning, we made our way to breakfast and met

one of the Doctors, the one who had come round in the night. His young daughter looked up at us from her pushchair. There

was no news. They had called Sky television - they didn't know what else to do. He turned away and I could see he was

going to weep.

People were crying in the restaurant. Mark Warner had handed out letters informing them what had

happened in the night, and we all wondered what to do. Mid-sentence, we would drift in to the middle distance. Tears would

brim up and recede.

Our daughter asked us about the kiddie club that day. She had been looking forward to their

dance show that afternoon. Jes and I looked at each other. My first instinct was that we should not be parted from our children.

Of course we shouldn't; we should strap them to us and not let them out of our sight, ever again. But then we thought:

how are we going to explain this to our daughter? Or how, if we spent the day in the village, would we avoid repeatedly discussing

what had happened in front of her as we met people on the streets? What does a good parent do? Keep the children close or

take a deep breath and let them go a little, pretend this was the same as any other day?

We walked towards the

kiddie club. No one else was there. We felt awful, such terrible parents for even considering the idea. Then we saw, waiting

inside, some of the Mark Warner nannies. They had been up most of the night but had still turned up to work that day. They

were intelligent, thoughtful young women and we liked and trusted them. The dance show was cancelled, but they wanted to put

on a normal day for the children. Our daughter ran inside and started painting. Then, behind us, another set of parents arrived

looking equally washed out. Then another, and another. We decided, in the end, to leave them for two hours. We put their bags

on the pegs and saw the one labelled "Madeleine". Heads bent, we walked away, into the guilty glare of the morning

sun.

Locals and holidaymakers had started circulating photocopied pictures of Madeleine, while others continued

searching the beaches and village apartments. People were talking about what had happened or sat silently, staring blankly.

We didn't see any police.

Later, there was a knock on our apartment door and we let the two men in. One was

a uniformed Portuguese policeman, the other his translator. The translator had a squint and sweated slightly. He was breathless,

perhaps a little excited. We later found out he was Robert Murat. He reminded me of a boy in my class at school who was bullied.

Through Murat we answered a few questions and gave our details, which the policeman wrote down on the back of a bit

of paper. No notebook. Then he pointed to the photocopied picture of Madeleine on the table. "Is this your daughter?"

he asked. "Er, no," we said. "That's the girl you are meant to be searching for." My heart sank for

the McCanns.

As the day drew on, the media and more police arrived and we watched from our balcony as reporters

practised their pieces to camera outside the McCanns' apartment. We then went back inside and watched them on the news.

We had to duck under the police tape with the pushchair to buy a pint of milk. We would roll past sniffer dogs, local

police, then national police, local journalists, and then international journalists, TV reporters and satellite vans. A hundred

pairs of eyes and a dozen cameras silently swivelled as we turned down the bend. We pretended, for the children's sake,

that this was nothing unusual. Later on, our daughter saw herself with Daddy on TV. That afternoon we sat by the members-only

pool, watching the helicopters watching us. We didn't know what else to do.

Saturday came, our last day. While

we waited for the airport coach to pick us up, we gathered round the toddler pool by Tapas, making small talk in front of

the children. I watched my baby son and daughter closely, shamefully grateful that I could.

We had not seen the

McCanns since Thursday, when suddenly they appeared by the pool. The surreal limbo of the past two days suddenly snapped back

into painful, awful realtime. It was a shock: the physical transformation of these two human beings was sickening - I felt

it as a physical blow. Kate's back and shoulders, her hands, her mouth had reshaped themselves in to the angular manifestation

of a silent scream. I thought I might cry and turned so that she wouldn't see. Gerry was upright, his lips now drawn into

a thin, impenetrable line. Some people, including Jes, tried to offer comfort. Some gave them hugs. Some stared at their feet,

words eluding them. We all wondered what to do. That was the last time we saw Gerry and Kate.

The rest of us left

Praia da Luz together, an isolated Mark Warner group. The coach, the airport, the plane passed quietly. There were no other

passengers except us. We arrived at Gatwick in the small hours of an early May morning. No jokes, no banter, just goodbye.

Though we did not know it then, those few days in May were going to dominate the rest of our year.

"Did you

have a good trip?" asked the cabbie at Gatwick, instantly underlining the conversational dilemma that would occupy the

first few weeks: Do we say "Yes, thanks" and move swiftly on? Or divulge the "yes-but-no-but" truth of

our "Maddy" experience? Everybody talks about holidays, they make good conversational currency at work, at the hairdresser's,

in the playground. Everybody asked about ours. I would pause and take a breath, deciding whether there was enough time for

what was to follow. People were genuinely horrified by what had happened to Madeleine and even by what we had been through

(though we thought ourselves fortunate). Their humanity was a balm and a comfort to us; we needed to talk about it, chew it

over and share it out, to make it a little easier to swallow.

The British police came round shortly after our return.

Jes was pleased to give them a statement. The Portuguese police had never asked.

As the summer months rolled by,

we thought the story would slowly and sadly ebb away, but instead it flourished and multiplied, and it became almost impossible

to talk about any-thing else. Friends came for dinner and we would actively try to steer the conversation on to a different

subject, always to return to Madeleine. Others solicited our thoughts by text message after any major twist or turn in the

case. Acquaintances discussed us in the context of Madeleine, calling in the middle of their debates to clarify details.

I found some immunity in a strange, guilty happiness. We had returned unscathed to our humdrum family routine, my

life was wonderful, my world was safe, I was lucky, I was blessed. The colours in the park were acute and hyper-real and the

sun warmed my face.

At the end of June, the first cloud appeared. A Portuguese journalist called Jes's mobile

(he had left his number with the Portuguese police). The journalist, who was writing for a magazine called Sol, called Jes

incessantly. We both work in television and cannot claim to be green about the media, but this was a new experience. Jes learned

this the hard way. Torn between politeness and wanting to get the journalist off the line without actually saying anything,

he had to put the phone down, but he had already said too much. Her article pitched the recollections of "Jeremy Wilkins,

television producer" against those of the "Tapas Nine", the group of friends, including the McCanns, whom we

had nicknamed the Doctors. The piece was published at the end of June. Throughout July, Sol's testimony meant Jes became

incorporated into all the Madeleine chronologies. More clouds began to gather - this time above our house.

In August,

the doorbell rang. The man was from the Daily Mail. He asked if Jes was in (he wasn't). After he left I spent an anxious

evening analysing what I had said, weighing up the possible consequences. The Sol article had brought the Daily Mail; what

would happen next? Two days later, the Mail came for Jes again. This time they had computer printout pictures of a bald, heavy-set

man seen lurking in some Praia da Luz holiday snaps. The chatroom implication was that the man was Madeleine's abductor.

There was talk on the web, the reporter insinuated, that this man might be Jes. I laughed at the ridiculousness of it all

and then realised he was serious. I looked at the pictures, and it wasn't Jes.

Once, Jes's father looked

him up on the internet and found that "Jeremy Wilkins, television producer" was referenced on Google more than 70,000

times. There was talk that he was a "lookout" for Gerry and Kate; there was talk that Jes was orchestrating a reality-TV

hoax and Madeleine's disappearance was part of the con; there was talk that the Tapas Nine were all swingers. There was

a lot of talk.

In early September, Kate and Gerry became official suspects. Their warm tide of support turned decidedly

cool. Had they cruelly conned us all? The public needed to know, and who had seen Gerry at around 9pm on the fateful night?

Jes.

Tonight with Trevor McDonald, GMTV, the Sun, the News of the World, the Sunday Mirror, the Daily Express,

the Evening Standard and the Independent on Sunday began calling. Jes's office stopped putting through calls from people

asking to speak to "Jeremy" (only his grandmother calls him that). Some emails told him that he would be "better

off" if he spoke to them or he would "regret it" if he didn't, implying that it was in his interest to

defend himself - they didn't say what from.

Quietly, we began to worry that Jes might be next in line for some

imagined blame or accusation. On a Saturday night in September, he received a call: we were on the front page of the News

of the World. They had surreptitiously taken photographs of us, outside the house. There were no more details. We went to

bed, but we could not sleep. "Maddie: the secret witness," said the headline, "TV boss holds vital clue to

the mystery." Unfortunately, Jes does not hold any such vital clues. In November, he inched through the events of that

May night with Leicestershire detectives, but he saw nothing suspicious, nothing that would further the investigation.

Throughout all this, I have always believed that Gerry and Kate McCann are innocent. When they were made suspects,

when they were booed at, when one woman told me she was "glad" they had "done it" because it meant that

her child was safe, I began to write this article - because I was there, and I believe that woman is wrong. There were no

drug-fuelled "swingers" on our holiday; instead, there was a bunch of ordinary parents wearing Berghaus and worrying

about sleep patterns. Secure in our banality, none of us imagined we were being watched. One group made a disastrous decision;

Madeleine was vulnerable and was chosen. But in the face of such desperate audacity, it could have been any one of us.

And when I stroke my daughter's hair, or feel her butterfly lips on my cheek, I do so in the knowledge of what

might have been. But our experience is nothing, an irrelevance, next to the McCanns' unimaginable grief. Their lives will

always be touched by this darkness, while the true culprit may never be brought to light.

So my heart goes out

to them, Gerry and Kate, the couple we remember from our Portuguese holiday. They had a beautiful daughter, Madeleine, who

played and danced with ours at the kiddie club. That's who we remember.

|

|

|

Exclusive: Who was the woman outside Maddie's flat?, 10 May 2009 |

Exclusive: Who was the woman outside Maddie's flat? Sunday Express

By James Murray

Sunday

May 10, 2009

A WOMAN was seen acting suspiciously outside Kate and

Gerry McCann's apartment just an hour before their daughter Madeleine was abducted.

The slim,

Portuguese-looking woman in a plum-coloured top and white skirt with long, dark, swept-back hair acted furtively when she

was spotted at 8pm on May 3 in 2007 near the Mark Warner Ocean Club complex.

She was standing under a streetlight

at a crossroads only 40 feet from where Madeleine was sleeping with her brother Sean and his twin sister Amelie.

Investigators are being urged to find her to see if she was in any way connected to a pockmarked prowler seen several times

outside the apartment in the day leading up to the kidnap.

Details of the mystery woman have only just become known

after a Sunday Express investigation into the baffling case was alerted by an elderly British woman who has lived in Praia

da Luz on Portugal's Algarve for more than 30 years.

Speaking from her villa near the Ocean Club, the woman,

who has asked not to be named, recalled: "On that night I went to the supermarket at the bottom of the road just before

it closed at 8pm.

"As I drove past the entrance to the Ocean Club I saw a woman standing opposite Apartment

5A the McCanns were staying in.

"Even at that time of night the streets were deserted, so I was surprised

to see someone there. I remember thinking it was unusual because it is just not the sort of place you would hang around.

"As I drove up to the junction she stepped around to the other side of the street lamp as though she didn't

want me to look at her. She was not carrying a bag or a mobile phone. I thought she might have been waiting for a lift but

no car came along while I was there.

"I turned right and could see quite clearly she was looking at Apartment

5A.

"As I approached another junction a small, brown car, with just one English-looking man in it swung round

and nearly hit mine."

When she heard that Madeleine had vanished she asked a relative to inform the police

about her sightings.

More than 30 people have so far phoned in about the artist's impression shown on a Channel

4 documentary last Thursday of a scar-faced man seen loitering outside the McCanns' apartment.

From Jeremy Wilkins statement:

Q. Relative to whether

I know Jane Tanner;

Jeremy Wilkins: 'Now I know her name, description

of the clothes and photos which I have seen in the press. At that time I knew of her as a member of the group but did not

know her name. I do not remember having seen her when I spoke with Gerry, but I believe I saw her when I first ventured out.

She was stopped on the street in front of one of the group's apartments when I passed her down towards the exit to my

apartment. I do not know if it was her apartment or not. I remember that she was wearing the colour purple.'

|

| Jane Tanner in her purple/plum coloured top |

*

Note: Wilkins states that he set out with his child between 8.15pm and 8.30pm.

|

|

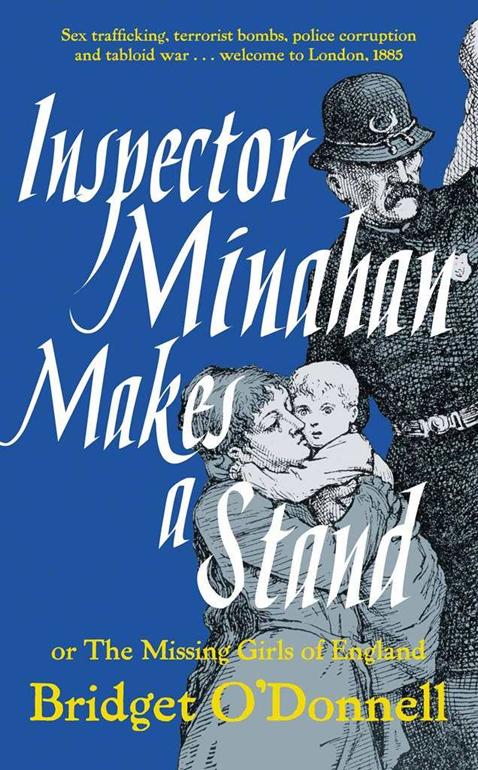

Inspector Minahan Makes a Stand: The Missing

Girls of England, 18 September 2012

|

|

Inspector Minahan Makes a Stand: The Missing Girls of England

Amazon

Bridget O'Donnell (Author)

Publication Date: 13 Sep 2012

Book Description

In Victorian London, the age

of consent was just thirteen. Unwitting girls were regularly enticed, tricked and sold into prostitution. If not marked out

for a gentleman in a city brothel, they were legally trafficked to Brussels, Paris and beyond. All the while, the Establishment

turned a blind eye. That is, until one policeman wrote an incendiary report. Disgraced for testifying against a violent colleague,

Irish inspector Jeremiah Minahan was transferred to the backwater of Chelsea as punishment. Here he met Mary Jeffries, a notorious

trafficker and procuress who counted Cabinet members and royalty among her clientele. Within days of reporting Jeffries, Minahan

was unceremoniously forced out of the Metropolitan Police. So he turned private detective, setting out to expose the peers

and politicians more interested in shielding their own positions (and peccadilloes) than London's child prostitutes. The

findings Minahan did reveal in 1885 sparked national outrage: riots, arrests, a tabloid war and a sensational trial . . .

other secrets were so fearful he took them to his grave, where they remained – until now. This is the true tale of a

man caught between a corrupt English Establishment and his own rebel heart: a very Victorian scandal, but also, a story for

our times.

About the Author

Bridget O'Donnell is a former BBC producer. She lives

in London. This is her first book.

|

|

|